The following essay is the third chapter of a book on the life and teachings of

Shakyamuni Buddha according to the Pali Canon and/or the Agamas that I have been writing since college. This particular part was written in 1995. I am

restricting myself to the Pali Canon and the Agamas in an effort to present

only what is likely to have been taught by the historical Shakyamuni

Buddha. While this essay and the others which constitute this work in progress are

informed by Mahayana and Theravada teachings, my main purpose was just to present what I perceive to be the most straightforward meaning of the

canon. In the future, I hope to cover the Mahayana canon in the same way.

Ultimately, I hope to take all this material and show how it does or does

not relate to the faith, teaching, and practice of Nichiren Buddhism as a source of common sense and spiritual guidance.

Namu Myoho Renge Kyo, Ryuei

Ryuei.net >

Pali Canon >

Mahayana >

Lotus Sutra >

Blog

The Human Condition

After teaching the four noble truths, the Buddha saw that the minds of the five ascetics still harbored attachment to the idea of self, the most

fundamental delusion. In order to remedy this, the Buddha taught them how

to finally relinquish the attachment to self by discussing the five

aggregates in terms of the three marks of existence.

“Monks, form is nonself. For if, monks, form were self, this form

would not lead to affliction, and it would be possible to have it of form:

‘Let my form be thus; let my form not be thus.’ But because form

is nonself, form leads to affliction, and it is not possible to have it of

form: ‘Let my form be thus; let my form not be thus.’

“Feeling is nonself...Perception is nonself...Volitional formations

are nonself...Consiousness is nonself. For it, monks, consciousness were

self, this consciousness would not lead to affliction, and it would be

possible to have it of consciousness: ‘Let my consciousness be thus;

let my consciousness not be thus.’ But because consciousness is

nonself, consciousness leads to affliction, and it is not possible to have

it of consciousness: ‘Let my consciousness be thus; let my

consciousness not be thus.’

“What do you think, monks, is form permanent or impermanent?” -

“Impermanent, venerable sir.” - “Is what is impermanent

suffering or happiness?” - “Suffering, venerable sir.” -

“Is what is impermanent, suffering, and subject to change to be

regarded thus: ‘This is mine, this I am, this is my self’?”

- “No, venerable sir.”

“Is feeling permanent or impermanent?...Is perception permanent or

impermanent?...Are volitional formations permanent or impermanent?...Is

consciousness permanent or impermanent?” - “Impermanent,

venerable sir.” - “Is what is impermanent suffering or

happiness?” - “Suffering, venerable sir.” - “Is what

is impermanent, suffering, and subject to change fit to be regarded thus:

‘This is mine, this I am, this is my self’?” - “No,

venerable sir.”

“Therefore, monks, any kind of form, whatsoever, whether past,

future, or present, internal or external, gross or subtle, inferior or

superior, far or near, all form should be seen as it really is with correct

wisdom thus: ‘This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.’

“Any kind of feeling whatsoever...Any kind of perception

whatsoever...Any kind of volitional formations whatsoever...Any kind of

consciousness whatsoever, whether past, future, or present, internal or

external, gross or subtle, inferior or superior, far or near, all

consciousness should be seen as it really is with correct wisdom thus:

‘This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.’

“Seeing thus, monks, the instructed noble disciple experiences

revulsion towards form, revulsion towards feeling, revulsion towards

perception, revulsion towards volitional formations, revulsion towards

consciousness. Experiencing revulsion, he becomes dispassionate. Through

dispassion [his mind] is liberated. When it is liberated there comes the

knowledge: ‘It’s liberated.’ He understands: ‘Destroyed

is birth, the holy life has been lived, what had to be done has been done,

there is no more for this state of being.’ “

(The Connected Discourses of the Buddha, pp. 901-903)

The four noble truths taught that passionate craving is the source of

suffering in this world and must be eradicated through the practice of the

Middle Way. This sermon, however, focuses upon the fundamental source of

craving, the false idea of a self. The four noble truths do mention the

five aggregates in passing, but they do not conclusively reveal the vanity

and perniciousness of the idea of a permanently abiding and happy self.

People have a tendency to be self-interested and self-concerned, but if

questioned as to what this self is they can only answer in terms of the

five aggregates. The body, its sense organs and the world it interacts with

are all part of form. Likewise, all of our mental and emotional functions

(including joy, anger, sadness, fear, love, hatred, desire, memory and

self-consciousness) can be grouped under the other four aggregates of

sensation, perception, volition and consciousness. The Buddha has pointed

out, however, that none of these five aggregates has any permanence, they

all function in a constant state of flux. Additionally, they must all

function in tandem. Any one of the five aggregates would be unable to exist

without the other four. This lack of a stable basis for existence precludes

any kind of peace or security which depends on something substantial and

abiding. The life of the five aggregates is a dynamic interrelational

process, and for one who seeks some uninterrupted satisfaction this process

can only be perceived as suffering. Because the five aggregates are

impermanent and lead to suffering they are said to be without a self.

Specifically, this means that one can not attribute to them the permanently

abiding and happy self that was the goal of the religious sages and mystics

of the Upanisads. A provisional self can be attributed in an

abstract way to the life process, but an actual thing or substance called a

self can not be found within the process. Nor can one meaningfully talk

about a self apart from the five aggregates because such a self would be a

mere abstraction with no substance or empirical reality to back it up. So,

the conclusion is that the five aggregates of form, sensation, perception,

volition and consciousness are characterized by the three marks of

impermanence, suffering and selflessness. In this way, the Buddha revealed

the vanity of the idea of a permanently abiding happy self. Once one ceases

to think in terms of such a self, then one is free from all the

compulsions, fears and desires which go along with the assumption that

there is such a self to find, protect or appease. One then becomes an

arhat, or "worthy one", who will no longer suffer from the cycle

of birth and death.

Not too long after teaching the five ascetics, now the five arhats, the

Buddha travelled to the banks of the Neranjara River in the country of

Magadha and there met the three Kashyapa brothers who were priests of the

fire god Agni with hundreds of followers. The eldest brother was named

Uruvilva Kashyapa and the Buddha requested of him that he be allowed to

stay overnight in the hall where the sacred fire was kept. Uruvilva was

dominated by superstition and arrogance and believed the Buddha was simply

a presumptuous ascetic who would be destroyed by the fire serpent which

lived in the hall, but he allowed him to stay there anyway. When the Buddha

emerged unscathed from the sacred hall the next morning, Uruvilva was very

surprised, but would not admit that the Buddha's wisdom and holiness was

any greater than his own. He was also afraid that the Buddha would try to

steal away his disciples. Finally, the Buddha pointed out that Uruvilva

would be unable to live a truly holy life until he discarded the envy which

lurked in his heart. Upon hearing this, Uruvilva was so impressed with the

Buddha's insight that he foreswore his fire worship and along with all of

his followers became disciples of Shakyamuni. The two younger Kashyapa

brothers and their followers soon did likewise. At this point, the Buddha

preached the Fire Sermon to them, so that they could elevate their minds

from the superstitious worship of fire to a true understanding of life and

the path to liberation.

“Monks, all is burning. And what, monks, is the all that is burning?

The eye is burning, forms are burning, eye-consciousness is burning,

eye-contact is burning, and whatever feeling arises with eye-contact as

condition - whether pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant -

that too is burning. Burning with what? Burning with the fire of lust, with

the fire of hatred, with the fire of delusion; burning with birth, aging,

and death; with sorrow, lamentation, pain, displeasure, and despair, I say.

“The ear is burning...the nose is burning...the tongue is

burning...the body is burning...the mind is burning...and whatever feeling

arises with mind-contact as condition - whether pleasant or painful or

neither-painful-nor-pleasant - that too is burning. Burning with what?

Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hatred, with the fire of

delusion; burning with birth, aging, and death; with sorrow, lamentation,

pain, displeasure, and despair, I say.

“Seeing thus, monks, the instructed noble disciple experiences

revulsion towards the eye, towards forms, towards eye-consciousness,

towards eye-contact, towards whatever feeling arises with eye-contact as

condition - whether pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant;

experiences revulsion towards the ear...towards the nose...towards the

tongue...towards the body...towards the mind...towards whatever feeling

arises with mind-contact as condition...Experiencing revulsion he becomes

dispassionate. Through dispassion [his mind] is liberated. When it is

liberated there comes the knowledge: “It’s liberated.’ He

understands: ‘Destroyed is birth, the holy life has been lived, what

had to be done has been done, there is no more for this state of

being.’ “

(The Connected Discourses of the Buddha, p. 1143)

The first thing to notice about the Fire Sermon is that it encompasses the

basic Buddhist categories of the six roots, the twelve fields, and the

eighteen elements which are used to analyse the components of human

existence. The six roots consist of the five physical sensory organs and

the mind, which perceives ideas and emotions. These six are called roots

because they are what keep us rooted in the world. We are constantly fed

sensory impressions which demand our attention and which feed the passions

like wood feeding a fire. The twelve sense fields are the six senses and

the six kinds of objects which correspond to them: forms, sounds, odors,

tastes, bodily sensations, and mental objects. The eighteen elements

consists of the six senses, their six objects, and the various forms of

conscious awareness which arise based on the contact between the senses and

their objects. For instance, when an eye sees a form there is a corresponding eye-consciusness.

The Fire Sermon also lists the three poisons of greed, anger and ignorance

(though Bhikkhu Bodhi translates them in this passage as lust, hatred, and

delusion) which arise in reaction to the impressions derived from the six

roots, twelve fields, and the eighteen elements. The three poisons are the

fundamental internal source of suffering.

The sermon then lists the sufferings of birth, old age (or aging), and

death which represent the universal fluctuation of life which will always

thwart the aims of the three poisons. The four sufferings which are

commonly referred to consist of these three with the addition of sickness.

This, in turn, leads to “sorrow, lamentation, pain, displeasure, and

despair”. All of this is what constitutes the burning which the Buddha

uses as a metaphor for dukkha, the state of suffering or

dissatisfaction which characterizes life. The Fire Sermon teaches that this

constant burning can be extinguished (the etymological meaning of Nirvana)

when one ceases to seek satisfaction through sensory experience and

practices detachment instead.

The Fire Sermon is important for many reasons. It not only clearly lays

out the case for detachment, but it also introduces the six roots, twelve

fields, and eighteen elements, and the three poisons, which will appear

again and again in other Buddhist teachings. Together they compromise the

fundamental sources of worldly suffering in Buddhism. Looking at them from

a scientific angle, we can see why the six roots and the three poisons are

not conducive to happiness. The six roots are the products of biological

necessity; they developed to assist survival not happiness. The three

poisons are the biological imperatives which demand that we use our minds

and bodies to seek food, avoid danger and ignore anything that does not

pertain to survival and the perpetuation of the species. One could say that

trying to find happiness or blissful repose through the six roots and the

three poisons is like trying to cool off on a hot day by swimming in a

bonfire. In some ways, Buddhist liberation is an attempt to free humanity

from mere biological necessity.

There is yet another way of understanding the vicissitudes of life in the

Buddhist teachings. In Buddhism, all sentient beings share the same life

process. Sometimes the phrase "four forms of birth" is used to

indicate all life which comes from wombs (mammals), eggs (birds, flies and

reptiles), moisture (bacteria) or metamorphosis (butterflies or spiritual

beings). The Buddha spoke of these in the Mahasihanada (The Greater

Discourse on the Lion’s Roar) Sutta of the Middle Length

Discourse:

“Sariputta, there are these four kinds of generation. What are the

four? Egg-born generation, womb-born generation, moisture born generation,

and spontaneous generation.

“What is egg-born generation? There are these beings born by breaking

out of the shell of an egg; this is called egg-born generation. What is

womb-born generation? There are these beings born by breaking out from the

caul; this is called womb-born generation. What is moisture-born

generation? There are these beings born in a rotten fish, in a rotten

corpse, in rotten dough, in a cesspit, or in a sewer; this is called

moisture-born generation. What is spontaneous generation? There are gods

and denizens of hell and certain human beings and some beings in the lower

worlds; this is called spontaneous-generation. These are the four kinds of

generation.”

(The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha, pp. 168-169)

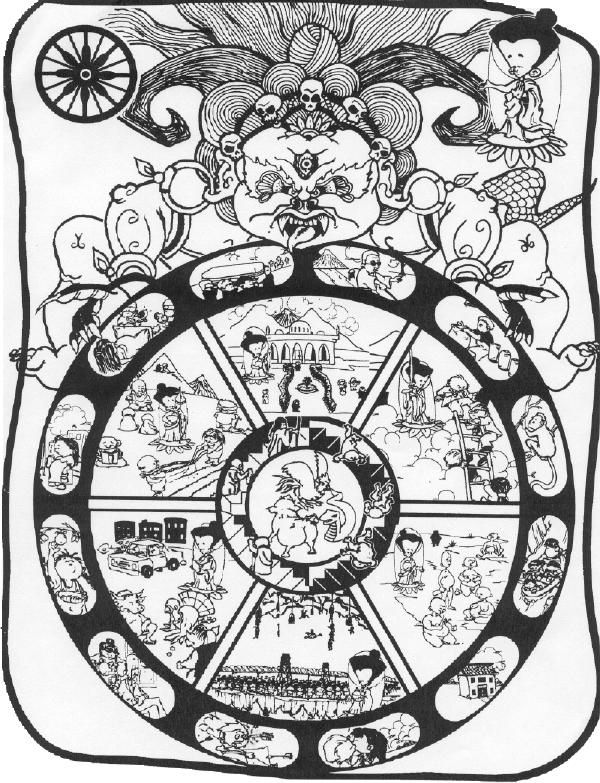

All life which arises from these four forms of birth can be said to follow

five different conditions or paths: the path of hell, of hungry ghosts, of

animals, of humanity, and of heaven. Sometimes the fighting demons would be

considered a part of the heavenly realm, but later tradition would view

them as a sixth path and would place them even lower than the human realm.

The early tradition also considered life as a ghost to be marginally better

than life an an animal. Presumably this was because one could retain a

sense of self-identity and rational thought. Later tradition would consider

the ghost realm to be more akin to the hell realm, though a little less

severe. These six paths are borrowed from the Vedic cosmology and refer to

the six realms through which living beings are said to transmigrate. They

are also indicative of the states of mind and ways of viewing and

interacting with the world based on one's habits, tendencies and

assumptions. All of these states or potential destinations of rebirth are

transcended through the realization of Nirvana. Following his review of the

four kinds of generation in the Mahasihanada Sutta, the Buddha also

spoke of the five realms and Nirvana:

“Sariputta, there are these five destinations. What are the five?

Hell, the animal realm, the realm of ghosts, human beings, and gods.

“I understand hell, and the path and way leading to hell. And I also

understand how one who has entered this path will, on the dissolution of

the body, after death, reappear in a state of deprivation, in an unhappy

destination, in perdition, in hell.

“I understand the animal realm, and the path and way leading to the

animal realm. And I also understand how one who has entered this path will,

on the dissolution of the body, after death, reappear in the animal realm.

“I understand the realm of ghosts, and the path and way leading to

the realm of ghosts. And I also understand how one who has entered this

path will, on the dissolution of the body, after death, reappear in the

realm of ghosts.

“I understand human beings, and the path and way leading to the human

world. And I also understand how one who has entered this path will, on the

dissolution of the body, after death, reappear among human beings.

“I understand the gods, and the path and way leading to the world of

the gods. And I also understand how one who has entered this path will, on

the dissolution of the body, after death, reappear in a happy destination,

in the heavenly world.

“I understand Nibbana, and the path and way leading to Nibbana. And I

also understand how one who has entered this path will, by realising for

himself with direct knowledge, here and now enter upon and abide in the

deliverance of mind and deliverance by wisdom that are taintless with the

destruction of the taints.”

(The Middle Length Discourses of the

Buddha, pp. 169-170)

The lowest of the six is the path of hell, which comprises eight hot hells

and eight cold hells. This state is reserved for those who are so consumed

with hatred and bitterness that their only wish is to destroy themselves

and others out of spite and the desire for non-existence.

The path of the hungry ghost is only slightly better. The hungry ghost is

said to have a large mouth and belly, but only a tiny throat. Hungry ghosts

can never be satisfied and they are consumed by craving. This is the state

of those who suffer from various forms of addictions which control and

dominate their lives. One's addiction can be for drugs, alcohol, sex,

gambling, power, work, entertainment or even religion; all these

addictions, however, are an attempt to cover up the fundamental sense that

life is suffering.

The path of animals is the state of cunning, primitive aggression and

instinctive desires. It is a state of mind that does not look beyond

immediate gratification and pays no heed to consequences or long term

benefit. Here, pleasure and pain reign supreme over reason and there is no

sense of morality. Though not as inherently painful as the first two

states, those who are in this state will inevitably meet with frustration

and confusion if not outright pain and suffering.

The path of the fighting demon originally referred to the arrogant demons

who tried to overthrow the Vedic gods in their arrogance. Those in this

state are full of pride and arrogance and extremely competitive. They can

never rest or feel secure because they must constantly strive to maintain

and improve their position and prestige.

The path of humanity is the state where suffering is recognized for what

it is, and morality and reason are called upon to ameliorate the human

condition. At this point, civilized life can truly begin. The human state

is considered a very fortunate one because reason is not dominated by the

sufferings and strivings of the four lower paths nor is it distracted by

the pleasures of the heavenly path. If reason remains strong and

unobscured, then one will be able to cultivate insight and attain the path of liberation.

The highest of the six paths is the path of heaven where the gods make

their abode. Unlike the Western concept of heaven, however, the Buddhist

heavens do not refer to a realm of eternal salvation. Rather, they are

temporary realms of bliss wherein all of one's desires are satisfied.

Though the highest of the twenty-eight heavens are indeed attained through

the cultivation of advanced states of meditative concentration or virtue or

devotion to the heavenly deities; these heavenly rewards for phenomenal

activities remain merely phenomenal states characterized by the three marks

of impermanence, suffering, and selflessness.

There are several important points which should be kept in mind in regard

to the six paths. The first, is that these are states of mind which all

people experience constantly throughout everyday life. They are all

interrelated and mixed; though each person tends to have certain states

which predominate. Next, the states of suffering from hell to anger lead

one to believe that suffering is inevitable or can be escaped through the

very things which cause it; while the state of heaven misleads one into

disregarding suffering as no great concern. Only in the human state is

there an equal tension between happiness and suffering. For this reason,

the human state is the most conducive to the cultivation of the path to

liberation. Finally, all of these are states wherein external phenomena are

allowed to determine whether one is happy or sad. However, the Buddha

teaches that through insight into the true nature of the five aggregates,

the three marks, the six roots, the twelve sense fields, the eighteen

elements, the four sufferings, and the three poisons one can cultivate

detachment and achieve liberation from the phenomenal world of the six

paths. In addition, this liberation, or realization of Nirvana, is

something that can be accomplished in this very lifetime.

The Wheel of Becoming (Skt. Bhavachakra; view enlargement)

Sources

|